PERSIAN MYSTICISM AND THE PRIMORDIAL LIGHT: SOHRAVARDĪ

Shihāb al-Dīn Yaḥyā Sohravardī (1155-1191), is one of the most outstanding exponents of the Enlightenment philosophy of all time. The originality of his thought lies in an attempt that could be described as dramatic, since he paid with his life the price of his ideas, to reconcile the Zoroastrian tradition before Islam with the legacy of Greek Peripatetic philosophy and Sufi doctrines.

©. Alfred G. Kavanagh. All rights reserved. Text given up, it may not be partially or totally reproduced by any analogic or digital means without the prior written consent of the author.

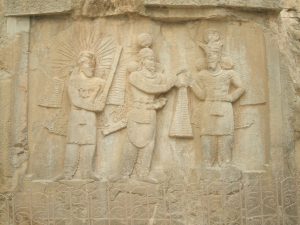

Coronation of the Sassanid sovereign Shāpūr II. On the right, Shāpūr receives the aura of the sovereignty of Ahūrā Mazdā, the supreme god of the Zoroastrian religion, escorted by the luminous god Mithras who holds the barsom, symbol of prosperity

From the air, after leaving behind Lake Van almost on the border between Turkey and Iran, the virtual map will unfold showing you the city of Khoy in Iranian Azerbaijan, the contours of Lake Urumieh on one of whose islands Hulagu Khan the Mongol emperor is buried he who destroyed the castle of Alamut; you will see Ardabil between the mountains of Sabalán; the city of Tabriz, possible location of the biblical Eden. To the west you will see the steep peaks of the Zagros mountains the natural barrier of more than 1,500 kilometers between Iraq and Iran. Even if it is possible for you at that moment to encompass the entire geographic complexity of Iran, when looking out the window, your first sensation will be the perception of intense light. The great Iranian mystic Sohravardi will turn this oriental light from the first instant of creation into the central nucleus of his thought.

Shihāb al-Dīn Yaḥyā Sohravardī (1155-1191), is one of the most outstanding exponents of the Enlightenment philosophy of all time. The originality of his thought lies in an attempt that could be described as dramatic, since he paid with his life the price of his ideas, to reconcile the Zoroastrian tradition before Islam with the legacy of Greek peripatetic philosophy and Sufi doctrines.

In the Zoroastrian conception of the world, the end of the combat between light and darkness will lead to the Fulfillment of the Wonder (Frashegird), at which time the resurrection of the dead and the Last Judgment will occur. To prepare for this moment, Zaratuštra announced in his hymns that in every millennium a savior (Saoshyant) would come to renew the world and put an end to death and lies.

Zoroastrian priest. 18th century European engraving

One of the great historians of religions, the former Archbishop of Vienna, Franz König, did not hesitate to point out to what extent Zoroastrian theology influenced the three monotheistic religions. The angelic hierarchies, which the Iranian mystic Sohravardī will take up centuries later, are largely based on the procession of yazatas, personifications of natural phenomena, who surround the throne of Ahūrā Mazdā. The heresies that arose within Zoroastrianism, such as Mithraism or Manichaeism, will exert a great influence in the Roman and Byzantine Empire, giving rise to numerous schools and sects that will struggle in the first centuries of the era with a religion that barely had a few followers, Christianity.

The explanation in the hermetic treatises on the reason for the creation of the world based on the Logos wishing to be known is comparable to a tradition (the hadith of the Treasure) attributed to the Prophet Muhammad “I (God) was an unknown Treasure and I wanted to give myself to be known, that is why I ordered creation and in this way I became known and men knew me”. In that initial moment, according to the hermetic doctrine, the dual character of the Logos, split into light and life, created another mind, the demiurge who in turn, created the seven administrators. These seven administrators correspond to the seven planets that order the destiny of all that exists, encompassing reality through concentric spheres.

Hermeticism shares with Indo-Iranian religious thought the identification of the word (logos) with the primordial light that allowed the unfolding of creation through different graduations of its intensity. It was Sohravardī, as we have noted, a true forerunner of interfaith dialogue, who sought common ground between the various civilizations and beliefs existing in the Middle East. He was named Sheikh Al-Maqtūl (the Assassinated Master) by his followers, as he was one of the martyrs of Sufism. He is considered the founder of one of the Sufi schools whose doctrine is based on an emanationist vision of creation from the primordial light (nūr al-anwār).

The solar wheel that surrounds the universal sovereign as an attribute of the light of divine glory corresponds to the concept of the khvarnah in the Avestan texts. This most beautiful light, described as the splendour of a thousand suns and which will constitute one of the pillars of Sohravardī’s philosophy of enlightenment, is a sign of divine favour that legitimizes the sovereign. While the king as vicar of justice and divine order guides the community along the path of Truth, material and spiritual prosperity guarantee him. However, when he succumbs to illegitimacy or lies, his aura disappears and he is available to anyone who wants to execute him for having betrayed his primordial pact.

It was not an abstract legality, but rather based on the link between the divinity and the Indo-European sovereign, as vicar. The loss of the sovereign’s aura subverts the social order, or rather, introduces a state of exception, which requires a heroic act, such as those performed by the protagonists of Ferdowsi’s Book of Kings to re-establish said order.

It will be Henry Corbin (1903-1978) one of the greatest experts in the currents of Shiism who will undertake the translation of the main works of Sohravardī from Persian into French, making it possible for their dissemination in the West. Influenced by Heidegger’s concept of hermeneutics, as it appears in the work Sein und Zeit (Being and Time), understood as the act of understanding a text in an experiential sense, from the being, Corbin will discover in this way that said deep similarity is experienced through a universal language based on what he would call the creative imagination, the universal archetypes that provide us with bridges to give presence to knowledge (gnosis) that is veiled. Few authors in Persian mysticism have shown such a deep knowledge of symbolism as Sohravardī, who will make use of the apparently very simple stories or parables, which, through the use of percussive images, will open the door to the reader that will lead him to the universal language of imagination.

* * *

Although much of Sohravardī’s work has not yet been translated into Spanish, we have the opportunity to read three accounts that are very representative of the thought of this author. Interested readers will be able to deepen their thinking by going to the original text “L’archange empoupré, quinze traités et récits mystiques” published by Fayard (1976) with a magnificent introduction by the translator himself, Henry Corbin. We have an excellent translation from French by Agustín López Tobajas of three stories from the original text, including El arcángel teñido de púrpura que da nombre a esta antología, El rumor de las alas de Gabriel y El Relato del exilio occidental:

Sihaboddin Yahya Sohravardi – “El encuentro con el ángel. Tres relatos visionarios comentados y anotados por Henri Corbin”(Trotta editorial, 2002)