Zoroastrianism and Christianity in Sassanid Persia

Zoroastrianism and Christianity in Sassanid Persia

MARCOS UYÁ ESTEBAN

Often one of the backbones of any civilization is religion, which sometimes plays a crucial role in the shaping and development of the state. In the case at hand, the Sassanid Empire, this axiom will be effectively fulfilled, since from the first moment of its creation, religion and State will go altogether hand in hand, represented in the figures of the priest and the monarch

We must go back to the beginning of the third century of our era to glimpse the origins of this symbiosis. In the year 224 d. C., the bases of the new Sassanid Empire will be established that will replace the previous Parthian Empire. Its new king, Ardashir I, will convert Zoroastrianism, also known as Mazdeism, founded by Zoroaster around the VII-VI century BC. C., in the religion of the new state declaring his faith in Ahura Mazda, god of wisdom, creator and promoter of the cosmos, to the detriment of Mitra, who had been worshiped by the Parthians. Much has been debated on why the adoption of this religion as the basis of the new power. Probably the monarch, to legitimize his new status, based his authority, as others did, on religion, which in ancient societies was deeply rooted and highly respected. In addition, he was to establish, as a pillar of support, good and close relations with the priesthood, and in order to receive their approval, Ardashir I offered them the religion of Zoroaster as the new official religion of the State, committing to spread it throughout all his territories, being the very priests in charge of this process. Another of the more plausible causes of this new adoption was the reestablishment of ancient Persian traditions dating back from the time of the Achaemenid Empire. Indeed, during the previous Parthian Empire, there was a certain relaxation of religious practices, where the tolerant attitude was one of the reasons why the Empire had influences from other religions, especially those referred to the Eastern cults and to the Hellenism, therefore, a religious recentralization based on doctrinal uniformity was necessary. On this last point, the adoption of a single institutional formula based on a single doctrine was also urgent. It seems that at the beginning of the Sassanid Empire, there were, as in the Christianity of the time, various currents that could be considered “heretical”. For this reason, the monarch and the priesthood were in charge of unifying Zoroastrianism based on common beliefs and practices that could be applied throughout the Empire, in order to prevent diversity from creating internal conflicts and various unorthodox forms of religion. The priest chief, Tansar, began to collect the different sacred texts that were scattered to unify them in a new version of the Avesta, a version that we have got to know today thanks to the compilation made in this period, based on oral tradition, that would culminate towards the sixth century, once a new phonetic alphabet was implanted that was of easier use instead of the previous consonant alphabet that was rather inadequate. However, it would be the great priest Karter who under the reigns of Sapor I, Ohrmazd I, Bahram I and Bahram II, was the one who really carried out the process of unification and institutionalization of the new religion, harshly oppressing those who opposed to Zoroastrianism, founding new seminaries known as Herbedestan, for the preparation of new priests and, in addition, established the cult of fire not only in Sassanid territory but even in other territories outside the Empire that were previously Achaemenid domain and that were in dispute with Rome, such as Armenia or Mesopotamia. The cult of fire was one of the important axes in the religion of Zoroaster, since fire meant purity and virtue, and for its followers, “reflection of the truth.” The rituals would take place in the so-called “fire shrines”.

As can be seen, it is clear that from the outset, Religion and State go hand in hand. In this sense, a tenth century Arabic text whose author was Mas’udi is clarifying: “My son, religion and royalty are brothers who cannot be without each other, because religion is the basis of royalty and royalty is the protector of religion. And if it does not have a base it collapses and what does not have a protector, perishes” (Murug I, 586). Here, Arhasdir I urges his son Sapor, the future Sapor I, to make religion his monarchical foundation and to show himself as a protector of religion. Despite this deep symbiosis that has been observed since the beginning of the Sassanid Empire, it is worth wondering if that close relationship really existed, that is, whether that so-called “State’s Church” of Zoroaster were its unique foundation. Ph. Gignoux maintains that most of the texts that allude to this belongs of the Arab-Persian tradition, composed after the fall of the Empire, which may suggest that this alliance between religion and the State was a literary device developed after the period Sasanian under Islamic influence, which tried to carry out, sometimes successfully, the symbiosis between the two powers. Surely there may be signs that Zoroastrianism was not adopted as the state religion and that there was not such a symbiosis. We must suppose that the first Sassanid monarchs either did not consider Mazdeism as their religious emblem, that is, as the bearer of their battle cry around which to rally the population in support of their reign, or that their vision of the Zoroastrianism may have been too lax, not so definite, even though they may have been devotees of Zoroaster by their own faith and practice. However, if we consider the close relationship between the two, it was not exclusive of the Sassanid Empire. As it is well known, shortly after, at the beginning of the 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine, despite not endowing Christianity as the official religion of the Empire, did establish a perfect connection between the two powers, which may be supposed to have happened as well in the Persia of the Sassanids.

Tras la muerte de Ardashir l, le sucedi6 su hijo Sapor I que mostró una apertura a la tolerancia de cultos de otras religiones minoritarias.

After the death of Ardashir I, he was succeeded by his son Sapor I (241-272), who, unlike his father, showed an openness regarding the tolerance of cults of other minority religions, but, nevertheless, such tolerance clashed with the rigid idea of the priest Karter, who thought that the unity of Zoroastrianism was above all other religions, which were persecuted by members of the priesthood, be they Jews, Christians, Nazarenes, Buddhists, Brahmins, Baptists or Manicheans. This last case, that of the Manichaeans, shows the great influence that the priesthood came to achieve not only within the religious power, but even in the decisions of the monarch. Indeed, the doctrines of Manichaeism, whose visible head was Maní, founded in Babylon, based on a universal cult associated with the rigid distinction between good and evil, between light, (Zmván) and darkness (Ahriman), between the spirit of man, considered to be of God, and the body, in the devil’s possession, were so much to the liking of the monarch that it was even thought of adopting it as the new state religion due to its more universal and popular character, therefore, the monarch ordered to Mani to exercise his doctrine throughout the Empire. The new Manichean church spread from Egypt to India, reaching the eastern borders of the Roman Empire. However, the great influence of the priesthood thwarted this possibility, and after the death of Sapor I, Karter himself managed to convince the new monarch Bahram I, of the Manichean threat, and had Maní himself captured and executed in the year 277.

That Sapor was more tolerant towards religious minorities does not mean he did not worship Zoroastrianism. During his reign, hundreds of “fire shrines” were built, highlighting the close relationship between men and gods. This propagation of dedications to the cult of fire was due to the monarch’s gratitude for the campaigns carried out in the western part of the Empire against Rome, reconquering ancient Roman territories such as Armenia or the fortress of Hatra, located in the Mesopotamian desert and even invading Syria. Karter, who accompanied Sapor I, was commissioned to reorganize the cult of Zoroaster in these places, but, nevertheless, we do not have reliable evidence that allows us to show that there was a proliferation of sanctuaries behind a need for expansion of the cult, but rather that the sanctuaries were erected, as we have said, to thank the gods for the success of the military campaigns. However, this served to further strengthen and reinforce the royal power if possible and also, by promoting Zoroastrianism in the newly conquered area, the monarch was possibly trying to unite his “nation” with his sights set on the battle against his Roman opponent in the West. This fact was not surprising, since especially, during the reign of the first monarchs, religious phraseology mixed with political instructions and slogans is very present in the first Sassanid royal inscriptions, such as an inscription of Sapor I that quotes thus: “I, Sapor, worshiper of the god Mazda, am king of kings of Eran and Anéran, whose origin comes from the gods, son of Ardashir, worshiper of the god Mazda, king of kings of Eran, whose origin comes also from the gods, and I am the grandson of the god Papak. I am the prince of the power of Eran”. The text makes it clear that the monarch claims some kind of genetic association with the gods for himself and his ancestors, that he affirms his position as a Mazda worshiper, and that he uses the terminology “king of kings” from the double division of the world, “Eran”and “Aneran”, referring to “Eran” as the lands belonging to the Sassanid Empire versus the “Aneran”, identifying those as non-Iranian lands. The claim that he and his father were both “Mazda worshipers” makes the monarch undoubtedly wish to have a reign in a stable political and religious position. However, this does not necessarily make him a person with great religious zeal and it does not have to suggest, although it is certain that the question is raised, that his kingdom was under a staunch religious unity. Perhaps, what emerges from this text is the use of the terminology “Eran and Aneran”, that is, the question of how the territories are divided into two parts, on the one hand, those that belong to the Empire, where religion prevails, and on the other, those that are not yet under Sassanid orbit, but that must be conquered to spread the Mazda cult. This, altogether with other activities of Sapor I, such as the recovery according to the Denkart, (the 9th century compilation of the theology of Zoroastrianism, in nine books, of which only the first two and part of the third survive), of books belonging to the Avesta scattered through Greece and India, all of those would form part of his religious policy where the priests acquired considerable power. The fact that Zoroastrianism became the official religion of the Empire facilitated the appearance of a fixed hierarchy and a clear differentiation in the priestly division that was accentuated at the end of the third century, comparable to the sphere of politics, where a few families nobles held high civil and military positions, in addition to the fact that the Zoroastrian religious community was based on a hereditary priesthood that remained within the same family.

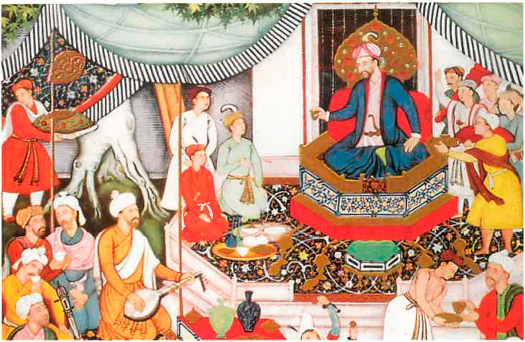

Miniatura que representa a un páncipe Persa con su corte. París. Biblioteca Nacional.

In the time of Bahram II (276-293), there was a turning point in the doctrine and evolution of Zoroastrianism. The new monarch, disgusted by consanguineous marriages, it seems, although it could rather be a Christian legend, that he embraced Christianity, but a short time later, at the instigation of Karter, he began to persecute not only the Christians, but also the Manicheans.

The first decades of the fourth century were especially tumultuous not only in the Sassanid Empire, but also in the orbit of its most staunch rival, Rome, on religious matters. In the year 297 or 302, according to the sources, in one of the many and endless Roman-Sasanian wars, the Roman emperor Diocletian published the so-called “edict against the Manicheans” against a religion that had been expelled from an Empire completely hostile to Rome, in an attempt, the Roman one, to reestablish the traditional cults in a period of crisis, as would happen in the four edicts that the same emperor formulated against the Christians, with the purpose, innocuous on the other hand, of converting the old Roman religion in safeguarding the crisis and on the subsequent resurgence of Roman power. In this period, under the reign of Narsés (293-302), the persecution of the Manicheans was suspended, and he became interested in them, but it was probably more for political than religious reasons, since he needed to secure numerous supporters on the borders of the Roman Empire, where the Manicheans were quite numerous. This attitude also favoured Christians, since we are not aware of any persecution during this time.

But it would be with Constantine the Great on the part of Rome, and Sapor II (309-379), on the part of Persia, when Christianity and Zoroastrianism became matters of state and reasons for confrontation between both powers. When Constantine made Christianity in 313, the official religion of the Roman Empire in all but name, the Christians residing in the Sassanid Empire were harmed by this new situation, creating an atmosphere of religious intolerance such as had never been seen before, motivated more by political than religious events, since the new unity of Rome threatened to break the Sassanid power. Faced with this situation, Emperor Constantine, in a letter gathered by Eusebius of Caesarea (Life of Constantine IV; 8-13), urges Sapor II to protect the Christians residing in his Empire, although it is not known for sure if this correspondence really existed. Perhaps Eusebius intended to represent the Emperor Constantine’s concern for Christianity, not only within his Empire, but also of those Christians outside of it. During the period that Constantine was emperor, until 337, there was a certain tolerance on the part of Sapor II towards the Christians, but just after the death of Constantine, a new Roman-Sassanid war was unleashed due to internal divisions among the sons of Constantine, divisions that the monarch tried to take advantage of without success. This caused Sapor II, in order to continue financing the war, to impose a double tax on Christians that many refused to obey, which led to a systematic persecution that ended with the slaughter of numerous martyrs and the destruction of practically all existing churches in the Empire. In the case of the Jewish minority, as there was no political determining factor, he had no reasons for their persecution.

But Sapor II wanted to go further and in another confrontation against Rome, this time against Emperor Julian, he recovered the Roman province of Armenia in 363, which had been taken away during the reign of Narsés. The monarch, once the new territory was pacified, made a serious attempt to reconvert those who had been baptized and therefore embraced the Christian faith, with a series of persecutions with the aim of attracting back the cause of Zoroaster to those who had reneged on the Mazdean cause. Churches and Christian places of worship were torn down, burned and razed to the ground in all regions of Armenia. It is the first case of proselytism, that is, the effort to win followers for a cause, the adherence to the cult of Zoroaster, which is recorded in the history of Zoroastrianism.

Yazdgi rd II intensificó la persecución a los cristianos y también a los judíos, sobre todo en Armenia en el 451. Judíos rezando. Londres. Museo Británico

But one of the most important confrontations between the followers of Zoroaster and the Christians, which began to take place in the fourth century but which would last until practically the end of the Sassanid Empire, was because of the almost insurmountable difference in form and pattern in the burial of the deceased. According to the Christian rite, the corpse must be buried either underground or in a place enabled for this purpose if it is an important person, so that it can become a place of worship, preferably in the form of inhumation; while in the Sassanian model, the corpse is not buried but is exposed in the so-called “rite of exposition”, whilst the Christian vision of this practice marks it as brutal and abominable, extolling the difficulties and martyrdom suffered by those Christians brave enough, who practiced burial within the boundaries of the Sassanid Empire despite prohibitions on doing so. The funeral practice of the followers of Zoroaster, collected in the Vendidad work, one of the Avesta writings, is based on the exposure of the corpse associated with the contamination it releases due to the putrefaction and decomposition of the body. Depending on the degree of pollution produced, it will be linked to your rank, be it religious or political. For example, a dead priest will release the so-called “nasu” or smell with more power, while if it is a farmer or a person of low social status, the smell will be much less. Non-believers, the case of Christians, will not produce contamination, which becomes ahrimanic creatures, incapable of contaminating the sacred elements or the earth. Many of the martyrs executed were left exposed at the place of execution, and the Christians buried them when they could. Even when the deceased was an important religious personality, be he a saint or a bishop, guard was mounted for fear that the remains would be extracted, taken and distributed to the faithful as something sacred in the form of relics that the Mazdean priesthood detested, firstly because they were used as the core of an unwanted devotion and consequently, a possible increase in the number of Christians and secondly, for the fear that some of these remains belonging to relevant figures of Christian life, could be considered as “nasu” despite being the corpses of non-believers. At the end of the reign of Sapor II, more than 160,000 Christian relics were accumulated in the Sassanid Empire.

The reign of Yazdgird I (399-420), which began shortly after the division of the Roman Empire in two, the West and the East, was dominated by an attitude of tolerance towards Christianity, if we look at the testimony of the historian Socrates Scholastic in his work Historia Ecclesiastica. In effect, the new monarch stopped the persecutions and ordered, through Bishop Maruta, of Armenian origin, to rebuild the ruined churches. Socrates emphasizes in his account (VII, 8, 1-20), the fundamental role that Maruta performed not only as a bishop, but as a Roman ambassador, which allowed the relations between Yazdgird I and the Eastern Roman emperor, Arcadius, to be cordial and friendly, and that would continue with Arcadius’s successor, Theodosius II. Maruta managed to establish an organized Christian community, which had been disintegrated after the persecutions of Sapor II and also, through the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon held in 410, made the Persian Christian Church have its own hierarchical organization and its own ecclesiastical law, and that in 424, achieved its independence until then under the command of the patriarch of Antioch.

This increase in the number of Christians did not go unnoticed by the Persian priesthood, who viewed with very bad eyes the policy of tolerance that the monarch exercised, which earned him the epithet of “sinner” on the part of his own. However, already at the end of his reign, and due to the pressure of the priesthood, the persecutions resumed again. The Greek ecclesiastical historian and in turn bishop of Cyrus, Theodoret, alludes, in his work also called Historia Ecclesiastica, the reasons for the persecution, due to the destruction of a shrine of fire of Zoroaster by Bishop Abdas, which provoked the wrath of the monarch and consequently that he ordered the destruction of all the churches of the Sassanid Empire, as well as the capture and execution of the Christians. It should be noted that the author judges the violation of a shrine of fire as an inappropriate and anachronistic act, in a context of pro-Christian attitude carried out by the monarch Yazdgird I for a long period of time (V, 39, 1-6 ). However, Theodoret also claims that the bishop’s misconduct was used as a pretext by the monarch in order to take action against Persian Christians, influenced by the priesthood, which allows us to think that tolerance towards Christians could have been more for political convenience than really out of respect for their religion.

The persecutions, which began during the reign of Yazdgírd I, continued under the rule of his successor, Bahram V (420-438), through Mihr-Sapor, the highest priest. Theodoret speaks of how Christians were tortured to death and the resumption of the ban on burial that many Christians violated under pain of martyrdom. However, in the third year of the monarch’s reign, in 422, a peace treaty was established between the Sassanids and the Eastern Roman Empire, mutually guaranteeing religious freedom between the Christians in Persia and the Zoroastrians in the Eastern Empire, which would last until the end of the monarch’s reign. In turn, Theodosius II, the Eastern Emperor, maintained considerable interest in the situation of Christians in the Sassanid Empire, for example, a bishop who had been tried and imprisoned for alleged robbery and usury was released as a result of his very own personal intervention.

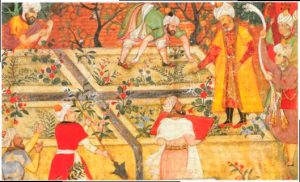

Los mazdakistas abogaban por la abolición de las desigualdades sociales como la supresión de la propiedad privada. Pintura s. XVI. Victoria &AlbertMuseum.

The fifth century in the Christian West was quite convulsed with the appearance of new currents that ended in heresy. Nestorianism stands out fundamentally, whose doctrine considered Christ separated into two persons, one human and the other divine, both complete in such a way that they make up two independent entities, two persons united in Christ, who is God and man at the same time, but forming two different people. Proposed by Nestorius, it was condemned at the Council of Ephesus in 431, where it was also discussed whether Mary, the mother of Jesus, was only the mother of Christ in the human and mortal sense, as the Nestorians said, or the mother of God in the sense divine. In the end, this second idea carried out by Cyril of Alexandria prevailed and the Nestorians were condemned as heretics. This condemnation had repercussions on Romano-Sasanian relations, which forced many Nestorians to take refuge in Persian territory. Already in 428, Bahram V had dethroned the head of the Armenian Church, replacing him with a Nestorian bishop, aware of the schism that was brewing within the Christian Church. Possibly it was a political maneuver, since considering the Nestorians also enemies and opponents of the Eastern Roman Emperor, they could use them for their own benefit, therefore, they were not persecuted, and from then on, the Nestorian Church would be almost the only Christian one existing and would even adopt some customs from the Zoroastrian religion. The other doctrine that appeared, Monophysitism, carried out by Eutyches, who only accepted the divine nature of Jesus, was not declared heretical. In the VI and VII centuries it would sometimes enjoy the favour of the Sassanid monarchs.

After the death of Bahram V, he was succeeded by his son Yazdgird II (438-457), who intensified the persecution of Christians and also of Jews, especially in Armenia in 451, after the deposition, on the part of the Church, of the Nestorian bishop thus ratifying the provisions of the Council of Ephesus. On the other hand, a sector of the Armenian population was in open rebellion against the authority of the Sassanids and their religion. The new monarch responded by launching a large-scale campaign of proselytism against the Christian population of Armenia and ordered the execution of some Christian clerics, taken prisoners in previous persecutions, and that were languishing in some prisons in various parts of the Empire. Yazdgird II was very popular in the Zoroastrian priesthood for his dedication to Zoroastrianism and the defence of funeral traditions, persecuting those who did not comply with them. In any case, it is difficult to understand the animosity that the monarch had after, according to Elisha, having studied all the religions of the Empire. During the reign of Yazdgird II’s second son, Peroz (459-484), Nestorianism completely disappeared from the Eastern Roman Empire, which would become the Byzantine Empire, after the fall of the Western Empire in 476. Indeed, the last Nestorians left Constantinople and opened their own church at Nisibis, naming Barsauma bishop. This had an impact on the way Christians were treated under Sassanid rule. The intolerance, as on previous occasions, was focused on the Armenian Christians and the Jews, especially in the Isfahan area, while Nestorians were treated with respect. Despite this privilege, the Nestorians did not change their point of view towards the funeral customs of the followers of Zoroaster, although, at least, after the divisions of the Christian Church, the Persian monarchs were somewhat more tolerant with the Christian burial tradition, evidenced in various later peace treaties with the Byzantine Empire, with clauses such as “freedom of burial for Christians residing in Persia”. Also during this reign, the great priest Mihr-Narsés, founded several sanctuaries of fire, especially in the district of Artaxser-Xwarrah. One of them he built in honour of himself, while three others were for his three children, one of them named Zurvandad, an indication, perhaps, of some Zervanist tendencies of his father, who had twelve thousand trees planted in his sanctuaries, a figure associated with Zurvanist cosmology.

Much of the VI century was dominated by the long reigns of two great Sassanid emperors, Kavad I (488-496 and 498-531) and his son Chosroes I (531-579). From the reign of Kavad I, a serious religious crisis stands out that occurred due to the appearance of Mazdakism, whose doctrines were largely inspired by Manichaeism. The new monarch, at the instigation of the Mazdak leader, Mazdak, adopted this new religion that offered great possibilities to change the foundations of society, since the Mazdakists advocated the abolition of social inequalities, especially the suppression of private property. The priesthood along with the nobility, obviously did not accept these changes and became allies to dethrone Kavad I, replacing him with his brother Jamasp.

Two years later Kavad I returned to the throne, and initially continued to support Mazdakism, but the state economy suffered, in part due to a new war against Byzantium, and therefore, seeing that it was impossible to establish an egalitarian society without the economy suffer for it, it finally wiped out the Mazdakists. From the reign of Chosroes I, thanks to the testimonies of Procopio from Caesarea and Agatía, we can know, even if it is only from the Christian point of view, the religious situation in the Sassanid Empire during this period, despite the fact that anti-Sassanid propaganda and a certain religious animosity is somehow exhibited. From Procopius of Caesarea we see that the funeral restrictions are increased again, and that for the first time, it is shown that a nation not subjected to the Sassanid Empire, such as that of the so-called Iberians (they refer to the Georgians, who were Christians), must follow the rules of the Zoroastrian religion. Chosroes I, writes to the Iberian king, Gurgenes, to demand a general adoption of Persian customs and prohibits his people from burying their dead in the earth, ordering them to be exposed (History of Wars, I, XII, 4). This is the first recorded case of mass proselytism outside Sassanid territory. In addition Procopio cites a case of funeral breach by a Zoroastrian nobleman, who was sentenced to death for burying his wife, although authors such as Christensen believe that his conviction was due to his adherence to Mazdakism. For his part Agatías, a follower of Procopio’s work, analyzes the customs of the religion of Zoroaster, although his observation is a bit impartial, his work (Histories or also called On the reign of Justinian) is important since it does not contain any reference to acts of religious intolerance against Christians such as forcing them to convert to Zoroastrianism and even reconverting those former followers of Zoroaster who had ceased to be so. This shows that during the long reign of Chosroes I, once Armenia and Iberia had been recovered and the Byzantine threat eliminated, there was no need to restrict the freedom of worship among those who were not belonging to Zoroastrianism, what shows once more that, at times, persecutions and religious intolerance were motivated more by political than by religious events. In any case, the Zoroastrian tradition gave Chosroes I the title of Anosarvan, “he of the immortal soul”, for making good religion triumph, despite the fact that his attitude towards Christianity was always hostile, he controlled the excesses of the pursuers.

The reign of the monarch Cosroes II Parvez (590-628), was the scene of a certain pro-Christian attitude. According to the Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocates, author of an eight-book work on the history of the Byzantine emperor Maurice, the fact that Chosroes II married a Christian woman whose later Persian literature has received much attention, becoming the subject of many Persian novels, reveals that the monarch made a favourable deal with the Christians (V, 14, 1-10). Syrian sources even give a detailed description of the wedding ceremony and allude to the fact that the bishops and the clergy were part of his entourage, and also Chosroes II built places of worship dedicated to Saint Sergius and Maía, the mother of Jesus. The name of the wife is attributed to Seirem and we find the most elaborate account about her in the so-called Chronicle of Guidi, which was composed in Syria around 660, the work of an anonymous Nestorian author, who probably wrote it in the region of Kuzistan. After the historiography of Theophylact Simocates there are few reliable sources that describe the events along the eastern frontier of the Byzantine Empire and its relations with the Sassanid Empire. Therefore, a source, such as the aforementioned chronicle, dating from the end of the Sassanid period, is extremely valuable. The text shows that Seirem’s wedding was also due to political factor and it is most likely that the marriage between Chosroes II and Seirem did not get the approval of the Zoroastrian priesthood as the marriage was against Sassanid laws.

Not only the wedding marked the Persian affinity to Western Christianity. In addition, the Patriarch of Antioch, Anastasius, consecrated three churches that had been built on the initiative of the Sassanid monarch, and it is even said, although it was highly unlikely, that Chosroes II may have worshiped Christian relics. According to Theophylact Simocates, when the Roman ambassador Probus, then bishop of Chalcedon, was sent to Ctesiphon, Chosroes II called him to the palace and asked to see the image of the Mother of God. He knelt in front of the image and affirmed that the represented figure had appeared to him and had told him that he would achieve the same victories as the great Alexander of Macedon (V, 15, 9-10). However, the claim that Chosroes II himself converted to Christianity is not supported by any evidence, despite the remarkable privileges enjoyed by Christians at this stage, confirmed by the excellent relationship with the Byzantine emperor Maurice, who, it seems, consented to the marriage between the Persian monarch and his daughter Maria. It is highly doubtful that this wedding ever took place, and for good reasons rather it seems that the many references to the union between Maria and Chosroes II are an expression of fictional literature based on the earlier marriage between Chosroes I and Seirem. The pro-Christian attitude of Chosroes II changed radically when the Byzantine emperor Heraclius invaded Sassanid territories. He persecuted the Christians, both Nestorians and Monophysites, and to re-establish Zoroastrianism, he founded three hundred and fifty-three shrines of fire. Despite this return to traditions, the Zoroastrian tradition condemns him as an unjust tyrant, unable to stop the religious crisis and therefore that of the Sassanid Empire. He was also not fair to the Jews, whom he had crucified when they aided Bahram VI in his attempt to access the throne. Finally, the collapse of the Sassanid Empire happened in the reign of Yazdgird III, when he lost the war against the advance of Islam. The Empire, depleted by the wars against Byzantium, was easy prey for the recently created Umayyad dynasty, which at least respected the Persian culture and religion with the translation of many of its books into Arabic.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOYCE, M.: “On the Orthodoxy of Sasanian Zoroastrianism” in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 59, No. 1 (1996), pp. 11-28.

DIGNAS, B. AND WINTER, E.: Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbours and Rivals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

GHAFOORI, A.: “The Sasanian Empire and Zoroastrianism: a Symbiotic Relationship” in Orient 2012: A Near and Middle East Civilizations Student Union Publication, University of Toronto (2011), pp. 29-34.

LVOV BASIROV, O. P. V.: Religious Intolerance and Proselitysation under the Sasanians. Online, pp. 1-20

POURSHARIATI, P.: Decline and fall, of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London; I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2008.

SARKOSH CURTIS, V. AND STEWART, S.: The Sasanian Era. The idea of Iran Vol. 3. London: LB. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2008.

SKJAERVO, P. O.: “Introduction to Zoroastrianism” in Early Iranian Civilizations, N. 102 (2006), pp. 1-68