The Safavid Shah Abbas and the Kurds of the Eastern Frontier

March 2025

The Safavid Shah Abbas and the Kurds of the Eastern Frontier

Abstract:

In this article, we will examine how the rulers of the Safavid Empire (1500–1736) related to the ruling Kurdish clans and how, despite their religious and social differences, they utilized them in the eastern provinces of the empire, which were then threatened by the Central Asian Uzbeks and the Mughals of India. We will pay special attention to the reign of Shah Abbas (r. 1587–1629) and his complex relationship with two of the most powerful Kurdish leaders of the time: Budag Khan Chegani and Ganj Ali Khan Zig.

Keywords:

Safavid, Kurdish, Qezelbaš, Khorasan, Qandahar

Introduction

In 1587, Abbas Mirza, one of the crown princes of the Safavid Empire, abandoned his seat of government in Herat and marched with a small army to Qazvin, the imperial capital, with the aim of removing his father from the throne.

The crown prince’s entourage included one of his trusted servants, Ganj Ali Khan Zig, whom the young Abbas Mirza affectionately called “baba” (father). Not far behind him marched the commander Budag Khan Chegani, one of the most important figures on the northeastern frontier and, therefore, indispensable to the prince’s coup attempt.

Abbas Mirza succeeded, removing his true father from power and initiating one of the most notorious reigns of the Safavid dynasty, which would extend until his natural death in 1629. In this article, however, we will focus on the aforementioned companions of the future ruler: were they members of the Kurdish tribal elite? If so, what were they doing in Khorasan, so far from their homelands? Had they abandoned the Sunni Islam of their homeland to serve a Shia ruler? How were the political careers of Ganj Ali Khan Zig and Budag Khan Chegani similar and different? And, finally, did Kurds continue to move to the eastern borders of the Safavid Empire?

Ganj Ali Khan Zig. (Wikimedia Commons)

1. Migration to Khorasan

The presence of the Kurdish people in the western provinces of Iran, as well as in the border countries that were once part of the Ottoman Empire, is well known. However, it often surprises foreigners to note that Kurds still live in Iran’s eastern province of Khorasan, and even in Afghanistan.

In North Khorasan and Razavi Khorasan alone, 696 Kurdish villages have been documented. They speak a Kurmanji dialect like the Anatolian villages and, unlike the latter, mostly profess Shia Islam and understand Khorasan Turkish due to their frequent contacts with other peoples in the region[1].

The origins of their presence on Iran’s eastern borders can be traced back to the rise of the Safavid Empire (1500-1736), famous for its militant Shiism and for having brought a Persian dynasty to power after several centuries of absence. Known for their ferocity, the Kurdish tribes of the western provinces had already been mobilized in the past to combat foreign threats (such as the Mongols), but the Safavid government went a step further.

The first Safavid shah, Ismail (r. 1500–1524), aimed to extend his rule far beyond Iran’s borders, and to achieve this he enjoyed the unconditional support of the Qezelbaš (Shia followers, mostly recruited from Turkic tribes), as well as a wide variety of tribes, including the Kurds. Shah Ismail was defeated by the Ottoman sultan (1514), and within a few years, the border between the two governments was formed close to the dividing lines of what is now Iran.

Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-1576), son of the previous ruler, faced the fact that the Kurdish tribes lived in a frontier land and that their loyalty to the Shah or the Ottoman sultan depended primarily on grants of autonomy and/or court favors. A review of his army in 1530 shows that out of 100,000 men (mostly Qezelbaš), only 15,500 Kurds were divided into six tribes; a significant but not decisive figure for the imperial army[2] [3].

The Great War with the Ottomans (1533-1555), although terribly destructive on the imperial borders, raised high expectations among some of the Kurdish tribes fighting for the Safavids, who hoped to increase their territory. At the end of the conflict, some of these tribes felt disappointed and quickly demanded new agreements. It is in this historical context that the Zig and Chegani clans, who were fundamental to Shah Abbas’s reign, began to emerge.

In a world where ethnic and linguistic criteria did not determine political projects and where peoples themselves intermingled, the very identification of the Chegani and Zig communities as Kurds has had its detractors:

The Zigs, who may have been partially displaced to Khorasan after the war, resided in the southern mountains of Giluyeh (a southern Iranian province currently home to a small Kurdish presence); and although the clan is identified with the Akrat, a common term for Kurds, it is not exclusive. Regarding the Chegani, categorized as a Kurdish group alongside the Zanganeh and Siyah-Mansur, they could also be considered Loris due to a Safavid court-style comparison[4]. Professor Oberling, on the other hand, citing O. Mann and Rabino, refers to the limited use of the term Chegani in Kurdistan and to the fact that the Gypsies of Astarabad (present-day Gorgan, near Khorasan) were called Chegani[5].

In any case, there was no major displacement of the ruling Ardalan clan (usually recognized as the walis of Kurdistan), but rather of smaller ones, dissatisfied with the 1555 agreements and required to move to more vulnerable borders. After a failed rebellion, numerous Siyah-Mansur clans were deported to the east and tasked with defending the border against the Turkmen tribes[6]. The Chegani, for their part, had been engaging in banditry, and in response to merchant complaints to the Shah, he ordered 500 of them to abandon their domains, although they eventually relocated to northern Khorasan[7]. These clans were joined by other clans that, decades later, became clients of the Zig or Chegani.

2. The Safavid Fitna (1576-1587)

While the long reign of Shah Tahmasp led to the displacement of numerous Kurdish tribes to the eastern provinces of the Safavid Empire, the reign of his sons allowed the great clans to ally with the various armed Qezelbaš factions. The autocratic Safavid power, briefly reinvigorated by Shah Ismail II (r. 1576-1577), was being challenged, with significant confrontations in Kabushan (Qučan, Razavi Khorasan), Herat, and Qandahar (Afghanistan).

In northern Khorasan, the Chegani clan had gained primacy over many of the region’s tribes following a failed Qezelbaš rebellion in the Khorasanid capital of Herat (1564); Budag Beg Chegani, opportunely positioned in favor of Shah Tahmasp, obtained from him government over the Chegani clan and the strategic fortress of Kabushan, north of Mashhad, which gave him influence over the affairs of the holy city and a decisive influence in the border war with the Uzbeks[8] [9].

In order to prevent possible plots by the Qezelbas on the periphery of the empire, which would require the use of princes of Safavid royal blood, Shah Ismail II (who had already executed his relatives in the capital) sent two trusted Qezelbas to control the cities of Herat (where Abbas Mirza was located) and Qandahar (where Muzaffar Mirza and Rostam Mirza, among others, resided).

Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu, the newly appointed governor of Herat, strove to maintain a good relationship with Abbas Mirza and appointed Ganj Ali Beg Zig as one of his trusted servants; such was their understanding that Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu was always revered by the prince, and Ganj Ali Beg was honored with the title of “baba” (father)[10]. When the order came from Ismail II to assassinate Abbas Mirza, the governor of Herat delayed carrying it out until, perhaps with his knowledge, Ismail II lost his life under mysterious circumstances, and the order was canceled.

In Qandahar, on the other hand, the situation did escalate violently due to the semi-independent nature of the city’s government and the fact that the local Qezelbas refused to cooperate with Shah Ismail II’s representatives, who failed to take Princes Muzaffar Mirza and Rostam Mirza into their custody. The shah’s loyalists appealed to Budag Beg Chegani for help in surrendering the castle, but he waited for reinforcements from other provinces, and, as in the case of Herat, the timely death of Shah Ismail II saved the princes’ lives[11].

The reign of Shah Muhammad Khodabanda (r. 1578–1587) marked an effort to return to the status quo of Tahmasp’s time: Abbas Mirza, the new shah’s son, continued to rule Herat alongside Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu; while the princes of Qandahar, under the protection of the Qezelbash Zulqadar, retained control of the Afghan city. Muzaffar Mirza, the prince who was to inherit Qandahar upon reaching adulthood, grew impatient with the Zulqadar regency and, instigated by Qezelbaš of his entourage and by several Kurdish tribal leaders (whose identity is not mentioned), tried unsuccessfully to eliminate his regent[12] [13].

Despite Shah Khodabanda’s good intentions, a factional conflict in Khorasan ultimately dragged the Safavid Empire into civil war and the proclamation of Abbas Mirza as sovereign. These rivalries reportedly began in 1577, when an Uzbek incursion across the border was crushed by the governors of Mashhad and Kabushan, Budag Beg Chegani. Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu, his superior as governor of the Khorasan capital of Herat, was deprived of the honors and riches that such a victory brought[14].

The Chegani leader was rewarded with the title of Budag Khan and strengthened his alliance with the governor of Mashhad, who in turn had important connections in Shah Khodabanda’s court. Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu, aware of his weakness at court and in Khorasan itself, crowned Abbas Mirza (1581) and attacked the Qezelbas who had sided with the ruler of Mashhad[15].

The coronation of Herat, which seriously undermined the imperial political project, prompted the dialogue-minded Shah Khodabanda to undertake a forceful military expedition against his son Abbas Mirza. The Chegani, who had tried to break the siege of Mashhad by Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu’s army, rushed to join Shah Khodabanda’s expedition[16]. Given the size of the Shah’s forces, Abbas Mirza’s commanders chose to retreat to their fiefdoms and wait for a better opportunity to counterattack. The Prince of Herat sent Kurdish spies to the royal camp at Taibad, but they were unable to discover what was being plotted; However, Khodabanda’s agents were able to gather crucial intelligence, and the shah’s army surprised his son’s army at Gurian (1583) and forced him to take refuge in the citadel of Herat[17].

Although Shah Khodabanda had cornered Abbas Mirza in Herat, an Ottoman invasion of the western provinces forced the ruler to negotiate a peace treaty highly favorable to the rebels: Abbas Mirza renounced the crown and, in return, Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu remained governor of Herat and it was decided to dismiss the loyal governor of Mashhad[18]. Shortly afterwards, the former rebel Morshed Qoli Khan Astaylu seized control of the holy city and quickly strengthened his ties with the region’s political leaders, including Budag Khan Chegani, whose daughter he married[19].

With Shah Khodabanda more concerned with the Ottoman threat than with other matters, a new conflict soon arose in Khorasan between the Mashhad faction and the Herat faction, whose leaders had not long before been allies. On this occasion, the governor of Mashhad, Morshed Qoli Khan Ástaÿlu, was able to seize control of Abbas Mirza and bring him to his city (1585). The prince’s new regent summoned all the emirs of the province, hoping to reconstitute the court, but had little success among members of the Šamlu clan[20]; one of the few of Abbas Mirza’s entourage who came to Mashhad was Ganj Ali Beg Zig himself, who was rewarded with the title of Ganj Ali Khan[21].

Soon after, political instability in the imperial capital and an Uzbek attack on Herat gave Morshed Qoli Khan Ástaÿlu the opportunity to revive Abbas Mirza’s imperial project, which had been buried in 1583. Together with the crown prince and a few hundred soldiers, the governor of Mashhad marched west and overthrew Shah Khodabanda (1587), effectively ending one of the most turbulent periods in Safavid history.

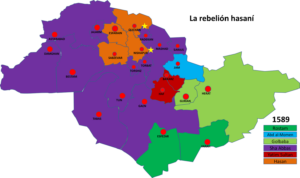

Rebellion of Budag Khan and Hasan Mirza (By the author)

3. The Reign of Shah Abbas

When Abbas Mirza definitively took the throne in 1587, he did so with the help of a heterogeneous coalition of Qezelbas and other tribal leaders from Khorasan organized by Morshed Qoli Khan Ástaÿlu. At that time, Budag Khan Chegani was already one of the most powerful warlords on the Central Asian border, while Ganj Ali Khan Zig was one of the most prominent figures in the young shah’s entourage. There is no record of any particular relationship between the two Kurds.

Disagreements soon arose within the coalition that had won the throne, primarily due to Shah Abbas’s need to rule the empire alone. He ordered the execution of Morshed Qoli Khan Ástaÿlu and seized the governorship of Mashhad from the latter’s brother. Then, to preserve the regional alliance network, he made Budag Khan Chegani governor of Mashhad, “amir al-umara” (commander-in-chief) of the Khorasan forces, and gave him custody of his newborn son, Sultan Hasan Mirza (1588). Despite his considerable rise, Budag Khan Chegani soon betrayed the shah.

The rebellion erupted shortly after Shah Abbas returned to Qazvin, having failed to organize an effective counterattack against the Uzbeks who had conquered Herat. Feeling left with little support in Mashhad, Budag Khan took his baby Sultan Hasan Mirza to Kabushan, where he enjoyed a significant tribal support base. The reasons for this decision are unclear: either it was a Kurdish decision, hoping to use Sultan Hasan Mirza (or another Safavid prince) and the coalition of Khorasan emirs to challenge a shah he considered unworthy; or it may have been a fear of his own deposition, as the Qezelbaš Ástaÿlu who had supported the shah against Morshed Qoli demanded that they keep Mashhad and the prince, and that Budag Khan be assigned to the western governorship of Hamedan[22].

In any case, it seems that Budag Khan’s sons had persuaded him to rise up against Shah Abbas. The ruler, fearing that the Uzbek invasion would be accompanied by a widespread rebellion by the Qezelbaš, sent one of his trusted men to Kabushan to try to reach an agreement and appointed an Ástaÿlu as administrator of Mashhad and amir al-Umara of the province[23]. Budag Khan rejected the shah’s orders and called on the emirs of the former coalition to march on Mashhad in the spring of 1589 and seize it from the Ástaÿlu[24].

The Kurdish warlord’s ultimate objectives are unclear, as by the time Eskander Beg Munshi’s official account was written, he had already been politically rehabilitated, so his most serious crimes may have been hidden. The fact is that, acting as Amir al-Umara of Khorasan and guardian of the heir apparent, Sultan Hassan Mirza, he did indeed assemble an army to conquer Mashhad from the loyalists of Shah Abbas. It is possible, given his friendly correspondence with rebels in the service of Rostam Mirza (a Safavid who competed with the shah), that he planned to proclaim a shah suited to his ambitions[25].

Budag Khan was unfortunate, as before he could attack Mashhad, an unexpected Uzbek expedition through Kabushan forced him to return to his fiefdom, and after a turbulent and avoidable battle with the Uzbeks, Budag Khan’s army dispersed in defeat. The Kurdish leader quickly reestablished contact with the Astaylu of Mashhad and, to reconcile with Shah Abbas, sent his son Hussein Ali to the court (probably bringing the infant Sultan Hasan Mirza with him)[26].

Shah Abbas did not forget the rebellion of his Kurdish subjects and soon invented a pretext to assassinate Hussein Ali Chegani and attack one of the clan’s encampments (1590). After the fighting, however, the Shah still needed Budag Khan to sustain the war against the Uzbeks in northern Khorasan, so he rewarded the Chegani’s eldest son, Hasan Ali, with the administration of Hamadan[27]. It was a timely decision because, in addition to conquering Mashhad with bloodshed, the Uzbeks advanced on the remaining cities of Khorasan, being held back in Esfarain for only four months by the Numantian defense of the Qezelbas and the Kurds (1591)[28].

The fighting in Khorasan continued for several more years, with neither Shah Abbas nor the Uzbeks able to gain a significant advantage: in 1596, Budag Khan Chegani was assigned to the border city of Esfarain, while his son Hasan Ali ended up in Bestam (present-day Semnan Province). Other members of the clan commanded in Sabzevar and Merv[29]. This involvement of the Chegani clan, and the absence of purges or rebellions, demonstrate their sincere commitment to Shah Abbas’s cause.

But Shah Abbas was not content with simply recovering the members of the former coalition that had brought him to the throne; If he wanted to expel the Uzbeks from Khorasan, he would need the full commitment of the governors of the nearby provinces. A clear example of this lack of cooperation was the Qezelbaš of the Afshar clan, who from Kerman had avoided getting involved in the Khorasan War, and when they did so in 1592, it was to the benefit of rival prince Rostam Mirza[30].

In 1597, Ganj Ali Khan Zig left the shah’s personal service and was rewarded with the governorship of Kerman province, which had been dominated by the Afshars since the beginning of the Safavid dynasty. With orders to place the province’s resources at the shah’s service and to rush his troops wherever necessary, Ganj Ali Khan transferred numerous Kurds to his governorship. The warlord Zig’s willingness led to his administration, a few years later, along with his sons Shahruj Beg and Ali Mardan Beg, administering a territory of 1 million km2[31] [32].

Barely a year later, the war for Khorasan reignited with great violence, with Hasan Ali Chegani dying in the battles of Bestam[33]. Fortune soon favoured Shah Abbas, as both the Uzbek ruler and his heir died, leaving the territories they had occupied in a state of virtual anarchy. The Safavid leader ordered Budag Khan Chegani to direct his forces against the Uzbek cities of Khurasan (northern Khorasan), while instructing Ganj Ali Khan Zig to advance on Herat[34] with whatever men he had available.

The Uzbek ruler of Herat, believing he was facing a lone initiative by Ganj Ali Khan, prepared for battle, but when the time came, he found himself facing Shah Abbas’s entire army. The Uzbek disaster of 1598 was massive, with the loss of all their conquests in Khorasan and some of their kings in Central Asia remaining in vassalage. After the successful campaign, Ganj Ali Khan returned to his rule in Kerman, and Budag Khan Chegani was briefly awarded the rule of Mashhad[35].

The relative pacification of the northeastern border meant a diminished presence of the Chegani in Shah Abbas’s official chronicles; but this was not the case for Ganj Ali Khan Zig, who held a position of great responsibility in the Shah’s eastern policy. Regarding the city of Kerman, he embarked on a very ambitious construction project in the center, which required the expulsion of families from the area. These families expressed their complaints to Shah Abbas, but the latter, after personally verifying his governor’s motivations, declared: “The complaints of the people end, the monuments remain.”[36]

In 1611, Ganj Ali Khan sent his Kurdish troops to the Baluchi lands of Makran, also becoming involved in the banditry in the city of Bampur. Two years later, he subdued the area’s tribal leaders, punishing the most recalcitrant and showing mercy to those who had converted to Safavid Shiism[37] [38].

Obeying Shah Abbas’s command, he sent his son Shahruj Beg or himself with troops to the wars against the Ottomans in the Caucasus, where his eldest son died accidentally in one of the campaigns. After the conquest of Qandahar (1622), Shah Abbas appointed Ganj Ali Khan Zig as the new governor of this strategic city. His son, Ali Mardan Beg, took over Kerman from then on, and when his father could no longer rule Qandahar (1624), he took over the city and was even honored by Shah Abbas with the title of “Baba II” (second father)[39].

Sha Abbas I and his court. (Wikimedia Commons)

4. Shah Abbas’s Successors

By the time of Shah Abbas’s death, Kurdish domains (interspersed with Qezelbaš Turks) had spread across the northern border of Khorasan, as well as in the strategic enclave of Qandahar, whose possession irritated the Mughal authorities in India. Shah Safi (r. 1629–1642), the grandson of the previous ruler, shared his imperial strategy but did not trust the same men.

The leader of the Zig clan, now known as Ali Mardan Khan, was well aware of the new shah’s hostility and soon began secret talks with the authorities of the Mughal Empire. After eliminating the remaining dissidents, Shah Safi demanded that the Kurdish leader return to the capital to account for his administration of Qandahar, but Ali Mardan Khan surrendered the city to the Mughal Empire and moved to India with his clan members (1638)[1] [2].

Despite this significant defection, the Safavid Empire maintained its policy of relocating Kurds to the eastern frontier, although no clan ever again held such positions of responsibility. Even after Shah Abbas’s death, some of the displaced tribes were gradually allowed to return to their homelands, resettling in places like Dersim (present-day Turkey) and bringing new religious traditions to the area, emerging from their contact with the Qezelbaš[3].

Shah Abbas II (r. 1642-1666), after aborting a projected alliance between Suleiman Khan (ruler of the Kurds of Ardalan) and the Ottoman Empire, took the precaution of exiling him to the holy city of Mashhad, while allowing his son to continue ruling the clan in the West[4]. Sheikh Ali Khan Zanganeh, a Sunni Kurd who served as Grand Vizier to Shah Suleiman (r. 1666-1694) for two decades, faced with evidence of political discontent and corruption in Kerman, appointed new Kurdish officials to his government[5].

With the collapse of the Safavid dynasty (1722), Kurdish war bands in the western provinces actively campaigned for one candidate or another to the throne, regardless of whether the candidate belonged to the Safavid imperial lineage. In Khorasan, the situation was not much different, and the clans of the northern border and Mashhad joined the court of Shahrukh Afshar (r. 1748–1796), a young man who owed the throne to his conquering grandfather (the famous Nader Shah) and to the fact that his mother was a Safavid princess. In 1750, the tribes of Mashhad, including Kurds, overthrew the ruler in favor of Suleiman II, who was also descended from the Safavids on his maternal side; although his control of the throne was short-lived, as many of the tribes eventually returned the throne to Shahrukh Afshar[6].

As we have seen, the Safavid strategy of moving Kurds to the eastern border was very common, both to ease political tensions in their homeland and to leverage their warlike tradition to curb incursions by steppe peoples like the Uzbeks. Although he was not the only ruler to do so, Shah Abbas relied on certain members of the Kurdish community, despite not being Qezelbash, to manage some of the region’s most important cities, such as Mashhad, Kerman, and Qandahar.

Notes

[1] Madih, A. “The Kurds of Khorasan”, Iran and the Caucasus, 2007, p.11

[2] Yamaguchi, A. “Shah Tahmasp’s Kurdish Policy”, Studia Iranica, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2012, p. 123

[3] Eskander Beg Munshi, contemporaneo del sha Abbas, de un listado de 72 notables del imperio safaví, identificó a 59 como turcos (gezelbash) y a 10 de, presuntamente, origen kurdo. (VVAA (trad. Minorsky, V.) “Tadhkirat al-Muluk: A Manual of Safavid Administration”, Edinburgh University Press, 1980, p. 15)

[4] Ibid, pp. 14-16

[5] Oberling, P. “Čegīnī”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, 1990, (https://iranicaonline.org/articles/cegini-or-cegani-a-tribe-that-originated-in-northwestern-persia-but-is-now-scattered-in-luristan-the-Qazvín-region-and-fa)

[6] Matthee, R. “Relations between the Center and the Periphery in Safavid Iran: The Western Borderlands v. the Eastern Frontier Zone”, The Historian, Vol. 77, 2015, p. 441

[7] Yamaguchi, A. “Shah Tahmasp’s Kurdish Policy” p. 118

[8] Oberling, P. “Čegīnī”

[9] Yamaguchi, A. “Shah Tahmasp’s Kurdish Policy”, p.118

[10] Ahmad Ali Khan-i Vaziri, “Tarikh-i Kirman”, Vol. 2, Saqafi Iran, 1997, p. 616

[11] En la cronica oficial solo es denominado Budag Beg, pero, debido a su presencia en la región, asumo que se trata del Chegani y no de un emir gezelbash (Eskander Beg Munshi (trad. Savory, R.), “Almara-ye Abbasi” (Vol.II), Westview Press, 1930, p. 351)

[12] En aquel periodo, las escasas oportunidades de promoción a puestos de la Corte llevaban a que clanes los relegados fueran más propensos a asaltos violentos al poder (Reid, J.J. “Tribalism and Society in Islamic Iran, 1500-1629”, Undena Publications, 1983, p. 52)

[13] Eskander Beg Munshi, “Almara-ye Abbasi” (Vol. II), p.653

[14] Qazi Ahmad Qomi, “Afzale Tavarikh”, Moaseseb entesharat wachape daneshgahe, 1984, p.674

[15] Mollayalaledin Mowayyem, “Tarikhe Abbasi shamele bagaeie darbar Shah Abbas Safavi”,

Publication Bahid, 1987, p.53

[16] Eskander Beg Munshi, “Almara-ye Abbasi” (Vol. I), pp.406-407

[17] Qazi Ahmad Qomi, “Afzale Tavarikh”, pp. 736-737

[18] Afushta Natanzi. “Naghavat-al-athar fisckre akhiar dar tarikhe safaví”. Ed. Ishraqi, I.

Bungah-i Tarjuma va Nashr-i Ketab, 1971, p.142

[19] Eskander Beg Munshi, “Almara-ye Abbasi” (Vol. I), pp.426-427

[20] Ibid, p.437

[21] Ahmad Ali Khan-i Vaziri, “Tarikh-i Kirman”, p. 616

[22] Qazi Ahmad Qomi, “Afzale Tavarikh”, p.886

[23] Eskander Beg Munshi, “Almara-ye Abbasi” (Vol. II), p.579

[24]Ibid, p.584

[25] Qazi Ahmad Qomi, “Afzale Tavarikh”, p.887

[26] No todos los emires optaron por volver a la obediencia al sha Abbas: hubo algunos que marcharon al sur del Jorasán para ponerse al servicio de Rostam Mirza (Eskander Beg Munshi, “Almara-ye Abbasi” (Vol. II), p. 664)

[27] Oberling, P. “Čegīnī”

[28] Eskander Beg Munshi, “Almara-ye Abbasi” (Vol. II), pp.617-618

[29] Oberling, P. “Čegīnī”

[30] Eskander Beg Munshi, “Almara-ye Abbasi” (Vol. II), pp.629-631

[31] Ahmad Ali Khan-i Vaziri, “Tarikh-i Kirman”, p. 618, 622

[32] Matthee, R. “Loyalty, Betrayal and Retribution: Biktash Khan, Ya’qub Khan and Shah Abbas

I’s strategy in establishing control over Kirman, Yazd and Fars”, Ferdowsi, the Mongols and the

History of Iran. Art, Literature and Culture From Early Islam to Qajar Persia. Londres: I.B.Tauris, 2013, p. 197

[33] Oberling, P. “Čegīnī”

[34] Eskander Beg Munshi, “Almara-ye Abbasi”, pp. 753-754

[35] Oberling, P. “Čegīnī”

[36] Ahmad Ali Khan-i Vaziri, “Tarikh-i Kirman”, Vol.1, p. 60

[37] Matthee, R. “Relations between the Center and the Periphery”, p. 441

[38] Ahmad Ali Khan-i Vaziri, “Tarikh-i Kirman”, p. 625

[39] Ibid, pp. 625, 627, 630

[40] Bernier, F. “Travels in the Mughal Empire (1656-1668)”, Oxford University Press, 1916, p.184

[41] Afzal Khan, M. “Ali Mardan Khan. A Great Iranian noble of Shah Jahan”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 44, 1983, p.199

[42] Suavi, A. “A Survey of the Roots and History of Kurdish Alevism: What Are the Divergences and Convergences between Kurdish Alevi Groups in Turkey?” Kurdish Studies Archive, No. 8, 2020, pp. 27-28

[43] Matthee, R. “Relations between the Center and the Periphery”, p. 448

[44] Ibid, p. 442

[45] Perry, J.R.,“The Last Safavids, 1722-1773”, Perry, Iran, Vol. 9, 1971, pp. 65-66